What does it mean for something to be digital?

Stories of digital identity

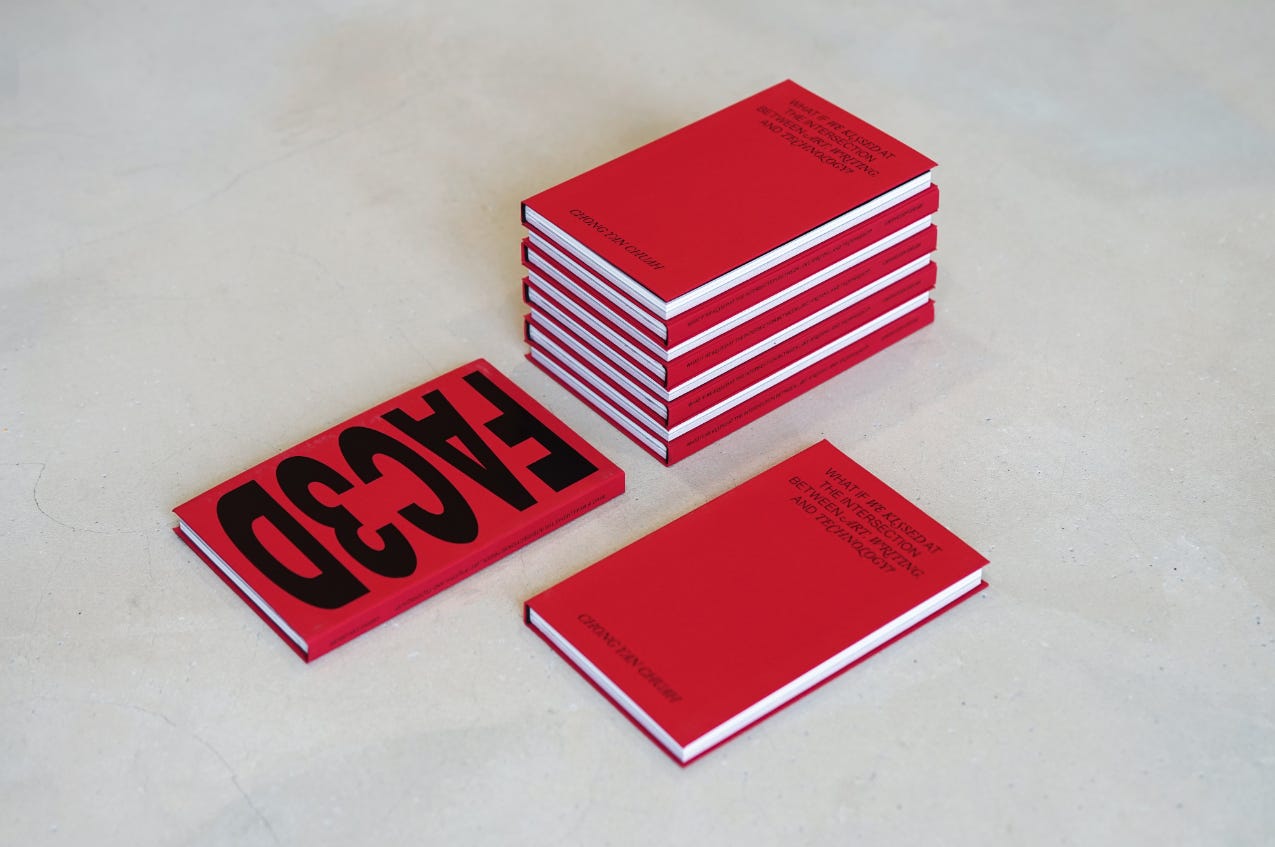

I first wrote this essay in 2021, for publication in FAC3D a collection of AI and human-penned essays all about digital existence. I’ve spent the week re-articulating the central theme of the xtended substack…and seeing as we (along with my new xtended.substack collaborator ) have landed on the idea that this publication is all about the changing meanings of the word ‘person’…this essay felt like a perfect place to start.

The essay in its entirety used three stories of different forms of identity to explore the shifting boundaries between digital and physical realities; how they are both equally real, all be it in different ways.

I’d like to share here the final of these three stories - about digital death.

Death, the digital, and digital death all have a lot to do with the central themes of the xtended anthology and what this substack will also be exploring.

Introduction

Half a century or so before Jesus was born, the Roman senator and philosopher Cicero wrote to a friend, complaining that he was being charged too much interest on a loan. The going rate of interest at the time was apparently 12 per cent. Cicero was being charged 48 per cent, and in his letter, Cicero exclaims that he understands the discrepancy between the two amounts because he can count them out with his digitos, his fingers. This is the earliest record of the latin word for ‘finger’. Through the evolutions of language, the word ‘digital’ came to mean a number that could be counted out on the ten fingers of two average human hands. Digital numbers are whole numbers. They are familiar numbers. The counting machines that became modern-day computers were referred to as digital because they worked on the simplest principles. They use just two numbers, zero and one; two absolute conditions of an electric current, on and off; and two default positions of the gates of a circuit board, open and closed, through which electricity passes. There is a simple, tactile reality to the digital processing that computers perform, grounded in principles that our own bodies, and our fingers, can help us understand.

And yet–

As I sit at my kitchen bench typing into a word doc with one of the strangest, most challenging, and computer-mediated years of collective human existence at my back, the word ‘digital’ fits into natural antithesis with words like ‘physical’, ‘tangible’ or ‘real’. By ‘natural antithesis’ I mean sentences that come up in FaceTime conversations with my Mum — “I want a real dog — not a digital one” or “I’ll send you digital flowers for your birthday — you don’t need to water them and they won’t die”.

When I’m talking to my mum, or a stranger at the supermarket, or some lawyer at a party who wants to buy me a drink, I listen as ‘digital’ slips into the semantic place of ‘virtual’ or ‘computer-generated’. We all seem to agree on what we’re talking about — roses that disappear when you turn off the computer screen, animals that don’t need oxygen or fresh air, faces that can’t be touched or poked or stroked. It is a blurring of conceptual boundaries and yet it makes sense; virtual cards and worlds and meetings, brought before our eyes and ears by digital processing done by a machine that thinks with two numbers.

Digital things can still be fingered, with the tip of your pointer on the screen of your phone. But they’re not graspable, in either sense of the word; the operative maths exceeds the understanding of almost everybody on the planet, no matter their number of fingers, and as anyone who has sent a hug over Zoom can attest, the digitally-rendered form of a lover is no substitute for the tangible, physical reality of clutching their arm and holding their hand.

No — digital realities and digital identities cannot take the place of physical form. Our human senses are too demanding for that.

If virtual and augmented perception is developed for multi-sensorial experience, then we might conceive of a day where our eyes, fingers, and tongues quiet their whispering with every pinch and swipe; “you’re not really there”, “it’s not really him”. But until that point, digital realities and identities must be developed as a way of being adjacent to the technique as old as the universe itself of just showing up as an arrangement of atoms in physical space. Digital realities have their own power and their own limitations.

To that end, through three stories of digital identities, I seek to draw out something of what this term can mean.

Digital Death

My father died a few years ago. Before he died, we used to talk on Facebook and when his death certificate had been printed and sent, I uploaded a copy to Facebook’s in memoriam request form and turned his profile into a memory site. I use it now to send him messages on his birthday, or when something happens in my life that I think he’d like to know about. It is a portal of communication to the soul of one I have lost, carried on the eyes of those who remain here, on earth, physically bound.

Digital Death is a practical concern. Facebook wouldn’t memorialise the page without government-certified evidence that my father had in fact died. To log into his other accounts, I leafed through a blue planner and guessed the current password from pages of crossed-out scribbles. When I managed to gain access to his Google Drive, I shared with myself all his folders of photos and the contents of his desktop, which I uploaded to the cloud. The majority of his accounts: his emails, Twitter, Myspace (I know), government gateways, banking, and so many others that I expect are tied to his name but which I never asked about (who asks their parents if they’ve ever signed up to Reddit?) for the majority of these accounts I did nothing at all. It didn’t occur to me at the time. Two years on it seems like too much work for too little gain. Instead, I gain comfort from the thought that he has inboxes still pinging and red notifications flashing, that there is a physical, manipulatable reality in some server farm somewhere storing messages from my dad, fragments of thought, fragments of self. The comfort lies in the concept of his own digital mark, a statement that he’s still out there, “I am (digitally) here”.

Preparing for digital death is becoming a numbered to-do point when writing your will. There are at least two social enterprises with social legacy kits and platforms you can use to record messages for when you die. If you have yet to encounter such services, my non-scientific assessment is that demand across the industry seems a little moribund.[19] Willing houses and funds is a process that people with such assets are (I’m guessing) motivated to think about, for the good of their families. But willing social accounts cuts close to the bone. Social accounts are intimate. They are quotidian, constant. They capture thought, emotion, and moment; they are records of our lives. It is hard to think about the future of such vivacious records. What good could they do, what could such artefacts possibly become?

What about a chat-bot? It’s a tested idea. The first application known to type with the syntax of the dead was Replika, trained on emails and messages from software developers and start-up founder Roman Mazurenko. Initial reviews from Roman’s close ones suggested that the machine-learnt network sent messages near-indistinguishable from the living man.

Replika isn’t a proxy for Roman, but the chat-bot wouldn’t exist without him and is now generating new content in a similar way that his living brain would. Roman and Replika overlap somewhat in identity space. In 2016, academic and data scientist Hossein Rahama trademarked Augmented Eternity. Over the course of their lifetimes, each person on the internet today could generate a trillion gigabytes of data. Could this be the material for a digital self? In one theoretical use-case, Rahama speculates that you could rent the digital avatar of an IP lawyer and avoid paying their $500 per-hour in-person consultation fee. In another, the digital selves of all the people you know became a suit of boutique Siris — ask one avatar for advice on pizza, another for advice on talking to men.

I wonder what digital avatars will be. Will they be property — owned in parts by the software company that generates and hosts them and the living body who provides the training data? Will managing my Digital Death become a matter of willing on my augmented self? Could digital avatars gain the legal status of persons? Companies are persons. Some rivers too. Practical immortality seems a bit closer with the thought of an avatar ordering flowers for your birthday and then messaging your sister, potentially even using your voice, as such replication is now technically feasible.

I do admit that when I imagine exactly this, there is a churning in my gut — a fear-based reaction to the uncanny valley of the digital self. And yet, the awareness that such technical possibilities may unfold many decades (in all luck) before my own death, has motivated me to exist online with more of myself. I am a weird person. I expect most people are. I talk to my vacuum cleaner and pretend to be a houseplant while sitting under tables. Sometimes, the urge to share such weirdness comes upon me and I reach for my phone — only to be stopped by an internal rubber band of constraint, “don’t be weird on the internet”. Why ever not? Any machine-learnt digital avatar of me will be all the poorer for not knowing my pet vacuum’s name (it’s Biscuit). I want my mimicry of houseplants and inanimate objects to be engraved on silicon disks in a deep-sea server farm, as permanent a contribution to the past and machine-learnt future of human society. This is the vision I have of a possible digital self — and if it’s ever going to exist with some semblance of the presence that physical reality naturally commands, I’m going to have to post better, record more truthfully, and use some kind of pastel-colored service to bequeath my account logins to someone when I die.