Understanding Whale

Decoding whale calls, talking to aliens, and having significant life moments beside a treadmill

You may already know that I’m reasonably obsessed with whales.

You may know this if you’ve spent more than thirty minutes with me in a semi-social setting. I would have found a way to bring it up. I am adept at shaping a conversation so that it quite naturally weaves its ways towards alternative careers, or subjects we enjoyed at school, or first jobs, or AI, algorithms, languages, animals, climate change, podcasts, books we’re currently reading or what we did during the pandemic.

Give me any of these topics - and in two sentences I will have you talking about whales.

My obsession takes a specific form.

I was not a child who knew everything there was to know about whales. I did not badger my parents to go on boats in search of them. I did consider studying marine biology for a time, but mostly because I was quite taken with the elegant form of the nudi branch.

My obsession with whales started only a few years back, when I - now undeniably a proper adult - was living in LA, working out in a dimly-lit gym, and breathing my own breath behind a surgical mask.

I was standing beside the treadmill. I was listening to a podcast (see! podcasts!)

It was then that I first heard the story that would spark my current yearning. And that really is the right word, yearning. You might know what it feels like, a desire to bury yourself in the world of an idea, to serve it without an agenda or any quest for fame or glory. This sounds religious, when I write it like this, and I wouldn’t be surprised if monks and nuns have felt something similar. On that day, if someone had asked me to give up my worldly possessions and follow the whales into the deep, I probably would have done it.

Ok. Tell us. What did you hear?

The short answer is that I heard an episode of a podcast about the scientific effort to decode the language of whales.

That is pretty cool.

Yes.

But is it cool enough to leave all your worldly possessions behind and jump into the ocean?

I honestly haven’t ruled it out, if it were ever a useful thing to do.

This story undeniably struck an existential chord within me.

My context in that moment is probably not insignificant. It was 2020. The pandemic was deepening, the city I lived in was locked-down, my head and news feed brimmed with human stories of sadness, kindness, bravery, and fear. I lived and live still a very human-centric existence.

I’ve never been the sort to structure my thoughts or schedule around lunar sightings, stone artifacts, or the geological history of rocks. I don’t know what it feels like to live that way, because I have always thought about and been mostly interested in human beings.

But at that point in time, I was craving something non-anthropocentric. Stories of whales felt like cool, clean water in my news-clogged brain.

And this story in particular just felt magical.

It’s like Dr Doolittle for grownups. Maybe it is because I’m not a moon theorist or expert in ancient rocks, but I feel acutely the lack of mystery and magic in the modern world.

Did you have that moment as a kid when you’d read or seen some story about explorers but when you got out a map to pick a place to explore, you realized that quite a lot of other adult people had gotten everywhere first, hundreds of years ago?

And even if you didn’t know how airplanes work, someone else did. The same goes for gravity and breathing and whether or not a thing can be invisible, and time travel and DNA and making cats turn blue in the future if they go near a nuclear waste storage hole.

There is no where and nothing left to explore, wailed my mind. Everything I’m interested in has already been discovered!

But of course I was wrong.

Because there is space. Where there might be aliens. And there is the sea. Where there are definitely whales.

Wow. Okay. This is getting really broad. You’ve had existential dread, the pandemic, Weber’s theory of disenchantment, and now aliens and whales. And I’m not even going to ask about the blue cats.

Oh you should ask. The blue cats are also very exciting. They’re connected to another subject area I find rather electrifying called nuclear semiotics.

But now is a good opportunity to actually dig into how people are using machine learning algorithms to decode the communications of whales.

And you’re going to somehow make that relevant to aliens?

Yes, that bit is actually easy. Although it makes more sense to do it later, once I’ve explained a little more about how people are trying to understand Whale and why it’s a really hard thing to do.

But to inspire some confidence that there is, in fact, a connection between the two - you know SETI?

The folks sending messages into space and listening for signs of intelligence from the stars?

Exactly. Well, the leading research organization for whale communication is also CETI.

That stands for the Cetacean Translation Initiative. But they one hundred percent made that connection on purpose.

Ok. I believe you. I will read on patiently waiting for the whale-alien connection to clarify. Maybe you could proceed with some more information about CETI?

Wonderful idea!

Project CETI is a US-registered not-for-profit organisation that was founded in 2020 by two marine biologists and national geographic explorers.

The organization commenced its work into the collection and analysis of whale communications in close collaboration with Roger Payne, the bioacoustician who (in the 1970s) recorded Songs of the Humpback Whale, a world-record-chart topping vinyl.

Songs of the Humpback Whale was, literally, a collection of humpback whale songs and was absolutely fundamental in igniting a global Save the Whales movement and turning the tide of public opinion against commercial whaling. So next time anyone asks ‘what is the point of art’ you can offer up that example, and then possibly feel slightly insecure about the potential global impacts of whatever art project you are currently working on.

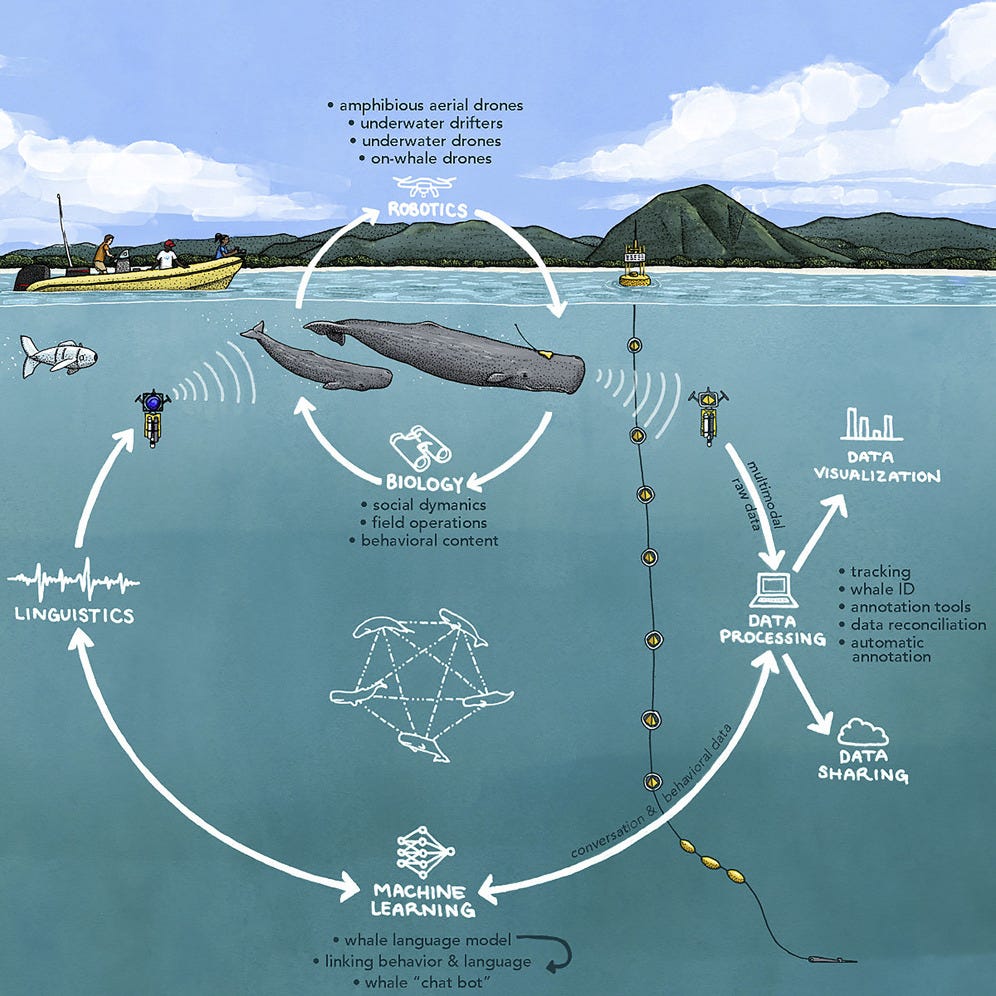

The many scientists and researchers now affiliated with CETI hold impressive degrees from impressive universities across the world, mostly in the fields of AI, machine learning, and robotics.

There is also a public GitHub repository of decoding-whale-related code that you can take a look at if that is your thing.

Currently, CETI is focusing specifically on decoding sperm whale communications and even more specifically, the communications of a population of sperm whales living in the waters of the Dominican Republic.

Their research efforts are dedicated to answering four key technical questions:

What are the building blocks of whale communication?

How are these building blocks combined?

How are these combinations of blocks then interpreted?

How does the context of the communication impact their interpretation?

Finding answers to these questions is really hard. The challenges are technical, labor-intensive, and also simply inherent to the unprecedented ontological magnitude of crossing the inter-species communication barrier.

I’m guessing that decoding Whale is more complex than learning another human language?

Yes. It is. But thinking about human languages is a good starting point for getting out heads around exactly why.

Consider all the things we need to know to decode language.

The building blocks of human languages are mostly sounds (phonemes). These sounds are then used to create blocks of meaning (morphemes).

Morphemes are words - but they’re not just words. They are the unit of meaning that can not be further divided and still retain their meaning. Here’s an example. The word ‘whales’ is made up of two morphemes. The first one is ‘whale’. ‘Wh’ or ‘ale’ or ‘hale’ no longer contain any meaning relevant to the concept of whales. To talk about whales you really need to use the word ‘whale’. The morpheme ‘s’ then implies plurality. You are talking about more-than-one whale. Whales.

The compositional rules of English dictate that plurality (in the case of talking about more-than-one-whale) is created by adding the morpheme ‘s’ on the back-end of the morpheme ‘whale’. You now have a plural noun that you can put into a sentence. How you arrange that sentence is dictated by English grammar. If you’ve learnt English as a second language then you will likely be able to give a better example than me of the challenges this entails.

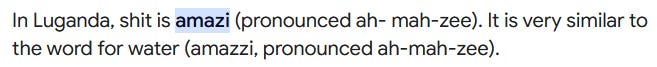

I’m instead going to give an example from learning Luanda - a language I do not speak but learned a little about when I was in Uganda.

Luganda has noun classes. Like gender in romantic languages, these classes affect how that noun is formulated in a sentence and how it reacts with verbs and adjectives. The classes come with their own prefixes and suffixes and ways to make the noun plural and negative. There are ten of them. Plus four extra categories of words that are not specifically noun classes but change how words work. Some examples of noun classes include Class II, which is mostly-but-not-exclusively things that are long and cylindrical. And Class V, which is mostly-but-not-exclusively big things and also liquids.

It’s pretty hard for an outsider to know which category any given noun might fit into.

And then there are the sonic complexities. Here’s a screenshot from Google that pretty much sums it up:

Right. ‘Ah-mah-zee’ as opposed to' ‘ah-mah-zee’. They’re completely different.

Fortunately, for English speakers trying to learn Luganda, there are resources and dictionaries and other human beings who can fall about laughing when you ask for a large glass of shit. Through charades and miming and pointing, humans can help other humans to establish a common vocabulary.

But imaging trying to learn a language when you can’t physically produce any of the sounds, or discern the difference between different sounds. Imagine if you didn’t share the same environment or biology or have any way of confirming that the thing you think you’re talking about is actually a thing that they would even recognise as a thing in the first place.

And now imagine trying to do that for a creature who comes from out of space.

Trying to understand Whale is the easier challenge compared to communicating with extraterrestrials, as at least we share the same planet. We’re all mammals. We live in families. We raise children. We need water. And when whales die we can take apart their heads and see the brains and auditory equipment that they use for making and receiving sound.

So the people behind CETI believe that there’s sufficient opportunity and shared context for decoding Whale to make attempting answering these questions worthwhile.

Ok. I understand now that decoding Whale is no easy feat. Might I enquire into how it is going?

CETI have outlined a process that they have peer-reviewed-reason to believe will enable the decoding of whale calls.

Aside from what I’ve dubbed the ‘ontological magnitude of crossing the interspecies communication barrier’, this process tackles the technical challenge of collecting a large enough database of sperm whale calls (called ‘codas’) to work with, and the labor challenge of analyzing all those those codas to draw out the sounds that might be whale phonemes and the combinations that could be whale morphemes.

Since 2020, many of the milestones have been in developing devices and methods to collect behavioral and sonic data, and machine learning algorithms to analyze it.

However; there have been a few exciting analytical developments as well.

Sperm whale codas are sequences of ‘clicks’. From a database of 9,000 recordings, researchers have identified discrete click-based phonemes that sperm whales are combining with different emphases and ornamentation into at least 156 discrete codas. These codas are then arranged with varying rhythms and tempos into sequences. A subset of codas have been found to identify the whale making the call. As for what the rest of the sequence means…science doesn’t yet know.

There is not yet enough evidence to equate what the whales are doing with their clicky-phonemes and combinatorial codas to human language.

A very excellent book I recently read (‘How to Speak Whale’, by Tom Mustill) dedicated a large number of pages to the debate of whether-or-not whales are even ‘talking’ at all, or if they’re just making sounds from some hard-coded biological instinct, which may indeed be complex, but not akin to a self-aware being looking out onto the world and finding meaning within it that they then encode into ‘words’ and ‘sentences’.

Tom Mustill, for the record, thinks that whales are talking. But it’s not a scientific consensus.

Evidencing meaning in whale communication is the ultimate question.

This what took my breath away, while I was standing beside the treadmill. The possibility of another people, another culture, a political domain, family trees, creation myths, science, even bigotry and xenophobia - is it weird that I’m so fascinated by the idea of xenophobic whales?

It’s a wide, big, open, deep question of mystery rich for exploring.

It’s a society of creatures who have as much right to this planet as we do.

It’s a society of creatures with rights in a rich mystery context that feels a lot like all the other people-things that I like thinking about (literature! art! whale art!)

Basically, if you’re not interested at this point…

Why am I still reading your rather long essay?

Exactly.

I am interested.

Good.

And I would like to read more. But later.

Fair enough.

Yep, I am indeed going to wrap this one up though, and continue at a later stage where I will take a closer look at the AI algorithms in practice, previous animal communication research, and exciting examples of non-human language in fiction.

Lovely.

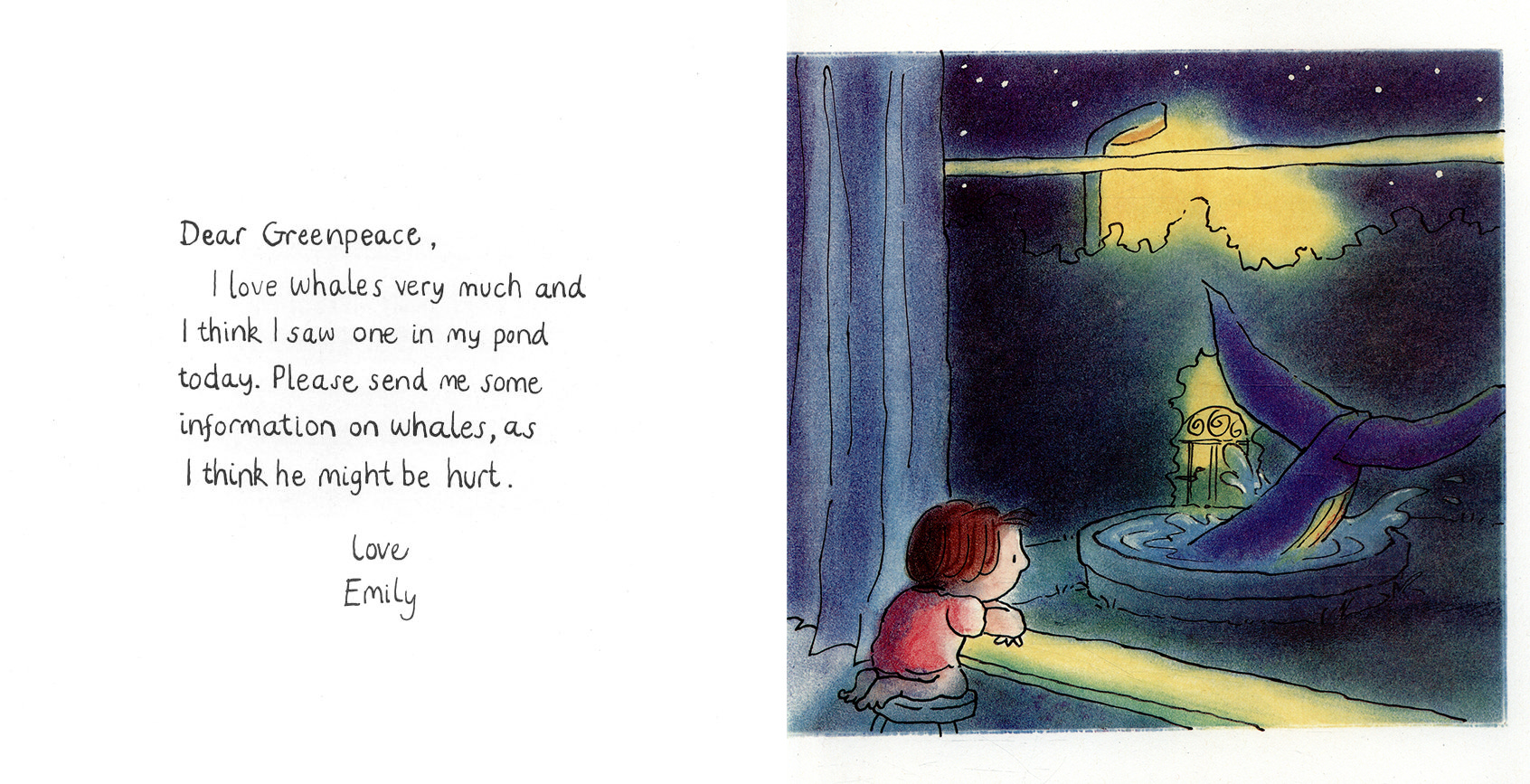

So here’s a final picture for you, of a book I just remember reading as a little kid:

Thanks for reading!

Oh wow, I learned quite a lot about sperm whale codas - and how lovely is your writing and genuine curiosity for whales 😍

I would say continue your own research and see if there’s any opportunities to go deeper!

I wanted to study the oceans and especially toothed whales since I was a child but took a different career root for different reasons.

And then, during 2020/2021 I made the decision to go back to university and study marine science ✨🤍🌊